The title is a reference to a total banger of a song by The Prodigy. Give it a listen if you want to get super pumped up while you read about biosecurity and habitat management. I wont mind if you take a few minutes to waggle your fingers or breakdance, whatever floats your boat…

Anyway this isn’t a rave-up. It’s a look at Invasive Non Native Species (INNS), how they can affect ecosystems, and how we can monitor and control them as a conservation group.

Recently, we found a Bearded Dragon (Pogona sp.) at Carew Manor Wetlands during some routine maintenance work at the site.

What a cutie!

This was obviously an escaped or dumped exotic pet. Bearded Dragons originally came from Australia, and are now a popular addition to British families who like feeding their pets live insects and risking catching salmonella (it’s true that many reptiles do carry the bacteria, but I actually find Bearded Dragons incredibly cute. Just look at that scaly smile and try not to fall in love! – Well worth the risk of runny guts). This makes the lizards non native, as they aren’t a part of our natural ecosystem. Non native (or ‘alien’) species are defined by the GB Non Native Species Sectereriat as ‘a species, subspecies or lower taxon, introduced (i.e. by human action) outside its natural past or present distribution’.

Our Bearded Dragon is not, however, invasive. We had to call a pet rescue center because it’s unlikely he would have survived very long in the wild here due to the temperature difference, among other factors. You’ll all be pleased to know that Forget Me Not animal rescue took Beardy in and did an amazing job rehoming him very quickly – best of luck little dude!

In order to become invasive, a non native species must establish a population ‘that has the ability to spread causing damage to the environment, the economy, our health and the way we live.’

Ring necked (or Rose Ringed) Parakeets – friend or foe?

An interesting distinction is that invasive species have to cause damage. Some non native species that become widespread don’t cause damage. Some can even benefit native species, for instance by providing cover.

A tree providing shelter for insects and birds is undoubtedly better than nothing for wildlife as long as it isn’t displacing a native tree that native species have developed a close relationship with over millennia – it’s when those natives become affected, unbalancing the entire ecosystem, that we get big problems.

One non native species that easily springs to mind for most of us living in Sutton is the Ring Necked Parakeet (Psittacula krameri), familiar to most of us as a deafeningly noisy denizen of parks and roadside trees across the borough, and indeed across much of the South East of England.

The parakeets are without a doubt non native, originating from Africa and India. We know that the current population of nearly 4000 breeding pairs are descendants of a small number of pet birds that either escaped or were released in the late 60s/early 70s. It is unclear, though, whether the colourful little chaps can be considered invasive.

Despite their increasing number and range (they have been sighted in every English county and have occasionally been seen in Scotland and Wales) there is no concrete evidence to suggest that they have negatively impacted our native species – but this is being monitored to ensure that with increasing numbers they don’t outcompete species occupying the same areas.

For truly invasive, damaging, species, there are a number that are very well known – and the costs to the environment and economy are immediately obvious.

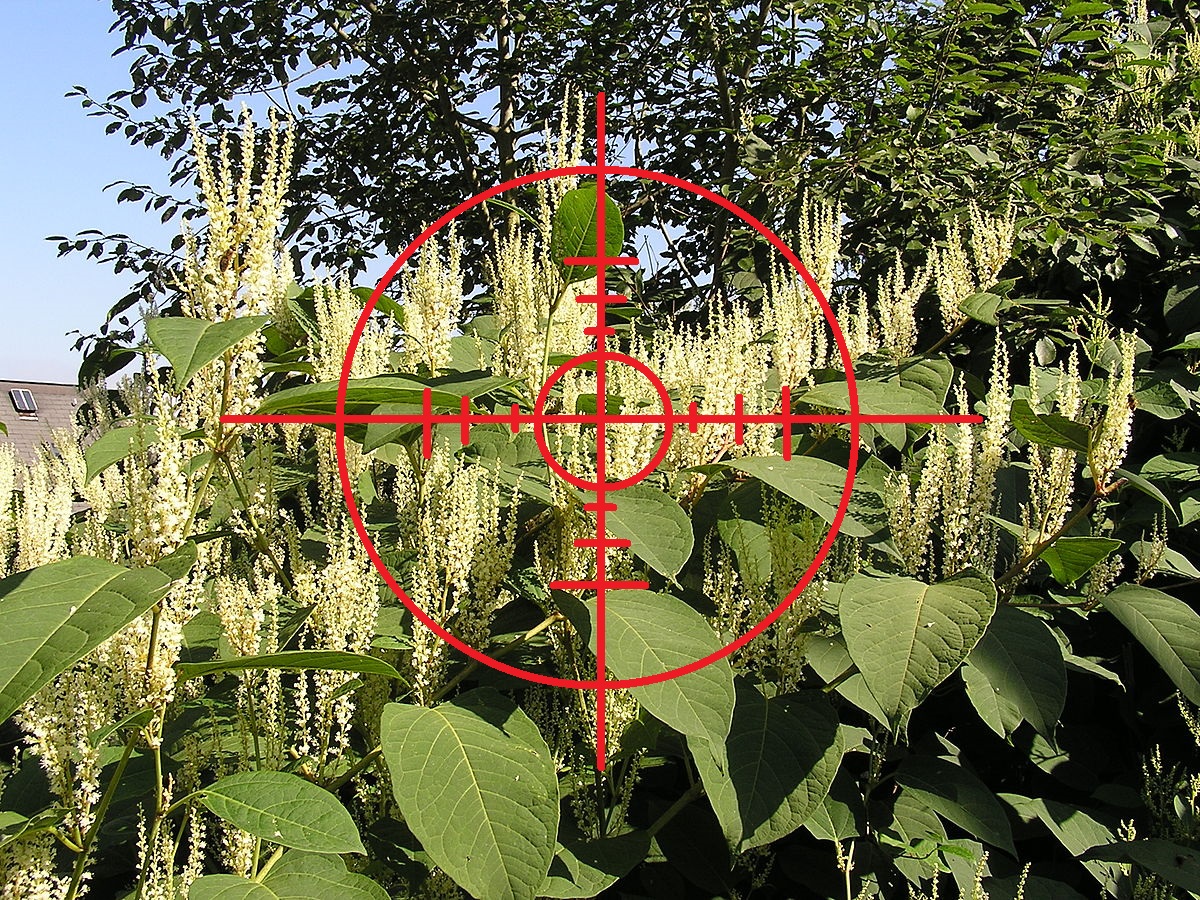

Japanese Knotweed – Cause for concern!

Of particular worry to anyone buying or selling a house would be Japanese Knotweed (Fallopia japonica) – a fast growing and incredibly hard to get rid of plant known for growing through concrete and causing structural defects in house foundations – even worse, most insurers do not cover Knotweed damage!

It forms dense stands anywhere it can, creating a huge network of roots called rhizomes and blocking light with its large, heart shaped green leaves. The seed of Japanese Knotweed is largely sterile and un-viable, but it instead spreads mainly through rhizome fragments. A tiny piece of root as small as a fingernail could grow into an adult plant.

This means it is spread incredibly easily by transference of soil – if someone were to mow an area with young Japanese Knotweed growth, then mow elsewhere without proper cleaning, it is likely that a small chunk could find it’s way to a different site.

Brought over from East Asia by Victorian botanists and gardeners for it’s (admittedly, quite attractive) broad green leaves and large white flowering spikes, it soon spread out of control and now costs £166 million per year. Ouch. More on this in a bit!

An aggressive, ruthless killer! Looks can be deceiving…

Rhododendron is another familiar plant, a pretty pink flowering bush which was brought to the UK from Iberia in the 18th century. Unfortunately the prettiness is only beaten by it’s intensely aggressive growth, as can be seen clearly almost anywhere it has colonised, but especially mountainous regions. Due to it’s thick, impenetrable canopy no other plants can grow under it.

On holiday to the Kintyre peninsula in Scotland a few years ago I barely saw another plant while there – that isn’t an exaggeration. I will say it was particularly beautiful watching the sun set over the sea, emblazoning the rhododendron-encrusted hillsides with a dazzling pink light.

Unfortunately, appreciation of aesthetics is (as far as I know) the preserve of humans, and the fact remains that those plants had a stranglehold on the environment, squeezing native plants and their associated fauna out of their natural habitat. Not cool, Mr. Rhododendron. Not cool at all.

I may have slightly doctored this image… it didn’t have a fence behind it originally.

Enough on plants, what about animal invasives? I already mentioned the ring-necked parakeet as a non-native species, but we also have a number of invasives that have actively damaged native populations.

So let’s talk Grey Squirrels… these cute, fluffy little rodents with a penchant for peanuts are very common across all of England and Wales, and are increasing their range towards the north of Scotland. Despite their cuddly appearance, the Grey Squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis), has a dark side. Many a native Red Squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) has felt the icy paws of death in the form of a larger, greyer cousin.

I mean okay, I might be making it sound like the Greys, incensed by a sadomasochistic rage – glint of manic depravity in their tiny, soulless black eyes – squeeze the life from the puny red victims squirming in their throttling paws, rushing with sick excitement as the last shuddering breath leaves the body. They aren’t that kind of killer. I highly doubt any squirrel has ‘gone on a bit of a spree’ as it were.

It has a halo cos it’s a little angel, but also cos they keep flippin’ dying. RIP little red dude 🙁

In fact, it’s far less sinister, more like accidental manslaughter (or squirrelslaughter I guess…). Through no fault of their own, Grey Squirrels are prone to harbour a disease called Squirrel Poxvirus. Grey Squirrels are unaffected by the virus, as they have built up an immunity. Red Squirrels do not have this immunity, although there are some positive signs that the Reds can develop resistance – there’s hope yet.

The disastrous effects of the disease, combined with the competition provided by the Grey Squirrels, means that our lovely native cuties have declined massively. There are now roughly 2.5 million Greys to 160,000 Reds. The Red Squirrel is now mainly confined to the highlands of Scotland, with some small declining populations further south and some island strongholds like the Isle of Wight, Arran and Anglesey.

Through the Poxvirus and competition, the Grey Squirrel has been a massively destructive introduction to the country, brought here from the Americas as a trendy, exotic addition to estates in the 1800s – it is also taking over much of Europe due to similar introductions in Italy.

An interesting complication comes when we consider what to do about invasive species. The obvious answer is to remove them. We’ve introduced a species, so it’s our responsibility to keep it in check or remove it entirely. Surely, if something is so numerous and aggressive that it threatens to make other species extinct, it needs bashing back to a controllable level, right?

Well, put those same parameters on the behaviour and distribution of Homo sapiens, and it might not be so simple. We’ve deliberately ruined habitats and killed off animals since time immemorial, with steadily increasing violence and intensity. Well done, everyone! A nice pat on the back all round (I hope the eye rolling sarcasm is perfectly evident through the screen).

I’m not actually suggesting we should treat people as an invasive species. The point is there are moral arguments for and against the culling and control of plant and animal species. These species have, with help from the human action of displacement, done very well by their own merits.

Unlike people, these species haven’t deliberated and carefully planned their domination over their ecosystems, they have basically just happened upon places they can thrive.

Knotweed in our sights! (We don’t really use guns though)

Unfortunately for those species, as a local nature conservation charity we need to do our best to keep our nature reserves functioning and as biodiverse as possible – which often does mean removal. I’ve never been set out on a squirrel slaughtering expedition, but some invasive plant species are regularly pulled and poisoned on our sites. Due to poisons being very poisonous, it is of course necessary that we take all precautions when using them. Through training in responsible use of pesticide and by exhausting other options before resorting to it.

The previously mentioned Japanese Knotweed is a menace. Its fast spread and dense coverage make it a constant battle to remove from sites that it would otherwise establish in and envelop, threatening to turn meadow and hedgerow into knotweed jungle. In previous years we have cut and burnt Japanese Knotweed in one site at Roundshaw Downs which seems to have kept it in check, but other areas have been growing and growing.

This year, armed with pesticide qualifications and lethal-looking injector guns we have attacked the knotweed canes on any of our sites it occurs. Roundshaw,Carshalton Road Pastures, Therapia Lane Rough and Sutton Ecology Centre all got a visit from Mark and I looking like stunt doubles from Ghostbusters. Japanese Knotweed is notorious for withstanding just about anything, but we hope that with repeat applications in